How a Jewish family and a museum are honoring an artist whose work remains nothing short of devastating

When Martha Kearns wrote the first English-language biography of the German artist Kaethe Kollwitz, she felt like she was alone. “So many people I talked to didn’t know who she was, this woman who was one of the greatest artists who ever lived,” Kearns told me.

That was 50 years ago. On July 8, at a small party at a Midtown Manhattan restaurant bar to mark Kollwitz’s 157th birthday, she declared: “I’m not alone anymore.”

She sure isn’t — because five decades after Kearns wrote Kaethe Kollwitz: Woman and Artist, which appeared in 1976, Kollwitz’s legacy has achieved what many observers would call the ultimate American art-world recognition: a major show at the Museum of Modern Art, which opened last March and includes many of the most powerful prints and drawings Kollwitz created, also a few sculptures.

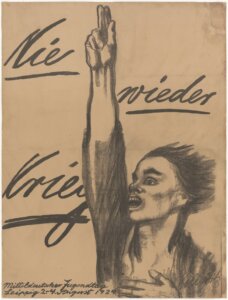

Works in the show, drawn from 30 different lenders internationally, offers a full view of Kollwitz’s socially conscious sensibility, and her command of printmaking that leaves one feeling almost defenseless against her images of revolution and war, riveted by her focus on the suffering and strength of women.

The widely praised MoMA show — The New York Times called the exhibit, which closes July 20, “dazzling” —includes a progression of self-portraits in which Kollwitz follows herself from youth to old age with a virtuosity that has led critics to compare her to Rembrandt.

The show’s curator, Starr Figura, a curator in MoMA’s Department of Drawings and Prints since 1993, was at the gathering at Cucina 8 ½ on 57th street. So was Jane Kallir, the owner of the Galerie St. Etienne, known for decades for showing Kollwitz and other artists from German-speaking countries. Kallir, 70, recently started the Kallir Research Institute, a non-profit founded to wind down the gallery’s activities, shifting to non-commercial priorities that include giving museums art from in-house inventory and her family’s collection.

The presence of Figura and Kallir made this small birthday gathering part of a bigger story in which the show’s end is also a beginning. It is about a Jewish family, art, and an historical shift at MoMA away from the strict early ideals of the Modernist movement for which it’s named and that have become limiting in the 21s Century.

Kollwitz was not Jewish. But art-minded Jews have long identified with her visual critique of injustice and violence. Kallir is the granddaughter of the late Otto Kallir, who arrived in this country in 1939 to flee from Hitler and did a lot to establish Kollwitz in America.

Now, Jane Kallir is enabling MoMA to obtain a significant trove of Kollwitz works from a collection her grandfather assembled starting in the 1940s, sometimes from fellow refugees who needed the money or wanted to detach from images of death and loss that had grown too personal. A few transfers were made just in time to be in the show; others are on their way to joining MoMA’s collection.

“I wanted to give MoMA a really great Kollwitz collection,” Kallir told me, in an interview days after the birthday event. “I knew Starr was interested. When the exhibition was announced, that clinched the whole thing for me.”

A total of 11 Kallir Kollwitzes will be Msgoing to MoMA, a combination of gallery sales and gifts from the Kallir family, the gallerist told me. She estimated their value is “probably in the low millions.”

To explain what MoMA is getting, Kallir described how the history of buying and selling Kollwitz’s work breaks into two main categories. One is defined by Kollwitz as mainly a maker of prints, creating (or having others mass-produce) copies of images. Those have been accessible to the public and collectors with modest means since early in her career, fulfilling her populist artistic ideals.

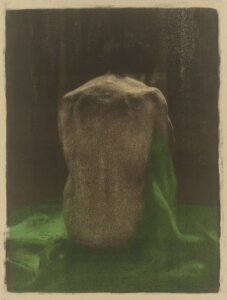

A more rarified Kollwitz market is established by working proofs that lure high-spending buyers enthralled by her process of repeated approaches to one print, her sensitive reworkings that make the road to her creative outcomes valued by itself. Collectors also covet Kollwitz drawings. All of the works MoMA is receiving fall into the second realm of drawings and revelations of the artist exploring her ideas, Kallir said.

The donations, she added, are being documented as being made, “In honor of Hildegard Bachert.” Also a Hitler refugee, Bachert worked for years assisting Otto Kallir at the St. Etienne, before becoming co-owner with Jane after he died in 1978. Bachert, who died in 2019 at 98, was a leading figure in the Kollwitz world, both soulful and businesslike regarding artists she cared about.

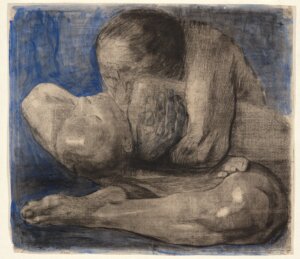

Figura, who said the gallery has been “very generous over time to MoMA and considerate of other museums,” credits Bachert’s effort in 2018 to help MoMA obtain an exceptional version of what might be the best-known Kollwitz print, “Mother and Child.” The monumental print holds an imposing place on a wall in the show with other prints of Kollwitz’s revising assaults on her wrenching image.

That wall, Figura said, “anchors the show.”

Kollwitz herself lost a son in World War I, and it jolted her to a life-long abhorrence of war that infused many pieces about what it did to men, women and children.

In a post-party telephone interview from her MoMA office, Figura said that the latest Kollwitz arrivals from Kallir holdings were helping to advance a change at MoMA that expands its mission beyond the original vision that Alfred Barr, its first director, had for the museum.

In 1936, Barr drew a sort of chart projecting how European Modernist movements had evolved and would define the purpose of his American institution. Tracing connections among different movements, it conveyed a conviction that art history was progressing from figuration to abstraction.

That chart “has definitely been very influential” at MoMA, Figura told me, but she said Barr also associated himself with German artists like Kollwitz who fought Fascism, and that the museum collected her work starting “as early as 1934.” She added that it “wouldn’t be fair to say that Alfred Barr or anyone at MoMA was against her.”

But Kollwitz didn’t win a loud shout of MoMA welcome, either. In the post-World War II era, other American museums, large and small, bought Kollwitz and staged Kollwitz shows. In New York, widely understood as the art world’s capital, the influential temple to Modernism had, before the recent Kallir transactions, only a modest group of Kollwitz works.

“We had 35 before,” Figura said.

“She did not fit neatly into the histories of Modernism,” she explained. “She is not a painter; she does not purposefully engage with abstraction; she wants her work to be available to everyone, not just to art-world insiders; she works in black and white. She is a woman who deals with women’s issues. And these are all things that would have put her to the side of Modern art history as it is traditionally told.”

Charting its way through changing times, MoMA is building out how it tells that history in the 21st Century, increasingly embracing women, African-American artists and others who have gone under-recognized in its narrative. Also, Figura said MoMA’s growing Kollwitz focus reflects a long-developing movement artists have made back to figuration.

Figura said Kollwitz is “in the forefront of our minds now,” and said she “expects” her work will appear in permanent collection galleries “more consistently than in the past.” Having the additional pieces, she added, makes it more likely the artist’s work will appear in future thematic exhibitions.

The Kollwitz show also marks a milestone for a Los Angeles dentist, Dr. Richard A. Simms, an African-American collector of work by both European and African-American artists whose lifelong passion for buying Kollwitz resulted in the foremost Kollwitz collection in the United States. Dr. Simms, 98, has been famously generous as a lender, and his collection has formed the core of several Kollwitz exhibitions. A 1992 show at the National Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C., to which Dr. Simms lent extensively, is regarded as the one that transformed Americans’ view of Kollwitz, highlighting her sheer power as an artist along with the force of her socially moving content that made her a staple for many young people in the politically charged 1960s era.

Dr. Simms passed his collection through a combination of gifts and sales to the Getty Research Institute (GRI), part of the Getty complex in LA, where it received a show in 2019 that revealed the full range of his acute collector’s eye. Still, the MoMA’s extensive use of his collection expands the impact of an American collector whose name remains largely unknown to many outside the world in which he exerted a major influence.

With nine pieces from his collection in the MoMA exhibit, Dr. Simms is its most significant lender.

Dr. Simms often found himself the only African-American in the room in a long journey through the upper reaches of the art world, including during his years as the only Black trustee of the Los Angeles County Museum of Art.

The MoMA catalog includes an essay by Sarah Rapoport about Kollwitz’s impact on other artists, including the major African-American artists Elizabeth Catlett and Charles White. But it contains no separate discussion of Simms beyond his name in the usual credit given to lenders. I asked Figura why, given Dr. Simms’ role in the show and his story of success as an African-American in the art world, the catalog didn’t give him more attention.

Figura told me that “collectors and the history of the private collection of Kollwitz is not something we were able to address” in the catalog. ”It just wasn’t in the scope of our project to talk about private collectors.

“I definitely acknowledge how important Dr. Simms was to the show, and the Getty was very generous to our exhibition, “ she added. She recalled her visit to the Getty, where she first saw in person a drawing Dr. Simms transferred to the GRI with the rest of his collection — of the German revolutionary Karl Liebknecht after his murder by right-wing killers on Jan. 15, 1919, a day that also saw the murder of Rosa Luxemburg.

Kollwitz was asked by Liebknecht’s family to visit the morgue in Berlin to draw his corpse. Her drawing hangs on a MoMA wall near a compactly epic woodcut the artist made showing working people paying homage to a Socialist martyr, a work as far from abstraction in form and purpose as any art could be, a signal of massive brutality no one could yet envision.

On Kollwitz’s 60th birthday, in 1927, many exhibits honored her work and Adolf Hitler was on the rise. On her 70th, in 1937, an admirer in New York offered to help her to a new life in America before it was too late. The offer came from Erich Cohn, a Jewish-American businessman who had amassed a large collection of her work, some of which he would sell to Otto Kallir.

The artist stayed in Germany, where the Nazis forbade shows of her art but spared her, and she died near the war’s end.

Kearns, the American biographer, spoke about this pattern with me as we stood on 57th Street after the party, discussing how the approach of America’s increasingly precarious election combines with MoMA’s new commitment to her work.

“Something important was always happening on her birthday, and here it is,” Kearns said. The one-time anti-Vietnam and Civil Rights activist, now in her 70s, spoke of her fears relating to the election and what might follow.

“We’ll get through it, whatever happens, we have her example,” she said. “Through World War I and World War II, all her losses, she suffered, but she stayed strong no matter what. That’s what she teaches us. That’s what her birthday is about.”

The post How a Jewish family and a museum are honoring an artist whose work remains nothing short of devastating appeared first on The Forward.

from The Forward https://ift.tt/hYl8mzN

Comments

Post a Comment