How Kamala Harris views antisemitism differently than Biden

At first glance, it is hard to spot much daylight between Biden and Harris on antisemitism. Biden drafted Doug Emhoff, Harris’s Jewish husband, to serve as his administration’s unofficial spokesperson on the issue. And the vice president’s office was deeply involved in creating the White House’s national strategy to counter antisemitism.

But there are significant differences.

A singular threat — or a universal one?

Biden has consistently described antisemitism as a unique menace. “There is no threat that worries me more than the rising tide of antisemitism,” said during a speech at the Brookings Institution nearly a decade ago.

He has decried the “delegitmization” of Israel and become fond of saying that Israel is the only thing keeping Jews safe, repeating this refrain just days before dropping out of the presidential race Sunday.

When Biden visited Yad Vashem, the Israeli Holocaust memorial, his takeaway was that, “for world Jewry, Israel is the light, for world Jewry, Israel is the hope.”

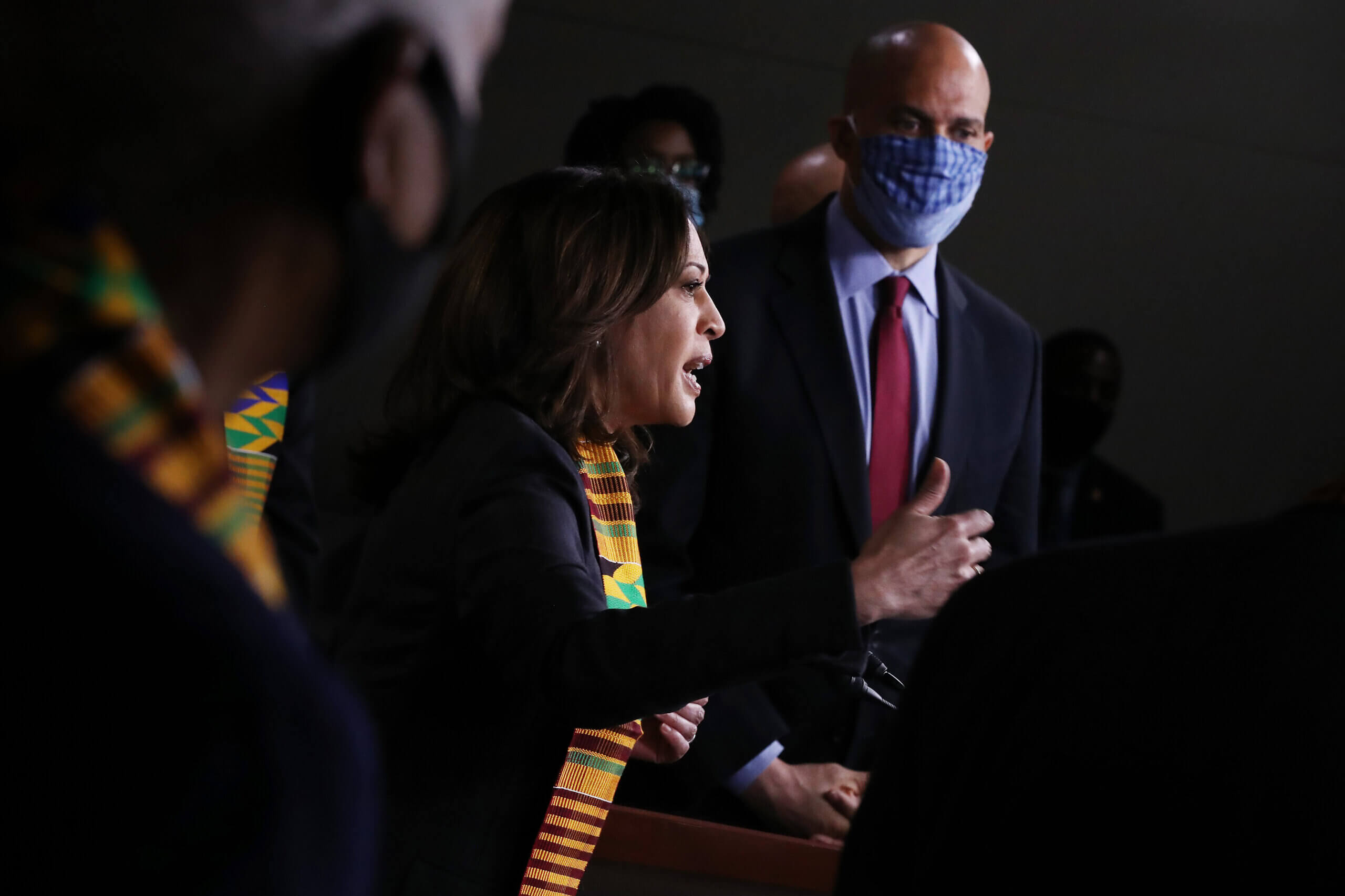

Harris, who is Black, Asian and female, speaks about antisemitism in more universal terms. “Let us always strive to remember that we as human beings have so much more in common than what separates us,” she wrote after her own visit to Yad Vashem.

Her statement about the fifth anniversary of the Tree of Life synagogue shooting in late October did not connect it to the Oct. 7 Hamas terrorist attack, as Biden’s did, and it concluded by emphasizing solidarity: “No one in our nation should be made to fight alone.”

Harris and Emhoff dodge controversy over Israel

Like Biden, Harris has sometimes tied antisemitism and Israel together. Back when she was California’s junior senator in 2017, she announced new hate crimes legislation during a speech to the American Israel Public Affairs Committee.

“As I fight to promote human rights and security,” she said, “Israel and the Jewish community will always be a priority for me.”

But in the nine months since Oct. 7, both Harris and Emhoff have been careful to stay away from the most contentious debates over whether strident protests against Israel are antisemitic. “When Israel is singled out because of anti-Jewish hatred, that is antisemitism,” both have said during multiple public appearances.

The mantra is borrowed directly from the national antisemitism strategy that differs slightly — but pointeidly from the controversial definition of antisemitism preferred by many leading Jewish organizations. That definition, from the International Holocaust Remembrance Alliance, holds that “applying double standards” to Israel could be antisemitic regardless of the motive.

The definition grates on many progressives who point to many reasons other than antisemitism — someone’s Arab, Muslim or Jewish heritage, for example — that a person might focus on Israeli human rights abuses.

The language that Harris and Emhoff use allows them to sidestep these concerns while still making a nod toward Jews who are worried about left-wing activism by offering an incontestable observation: protests against Israel are antisemitic when they’re motivated by antisemitism.

This tactic is in keeping with Emhoff’s approach, as the White House’s most visible spokesperson on Jewish issues, of embracing antisemitism as a unifying cause for American Jews while refusing to draw any clear lines around criticism of Israel.

“We had hours and hours of off-the-record conversations with him in the evenings and he was very candid about a lot of things, but was definitely not willing to go there,” said Laura Adkins, the Forward’s former opinion editor, who traveled with Emhoff to Poland and Germany last year.

Harris shows more sympathy to protesters

Harris has gone off-script a few times to express sympathy with pro-Palestine student protesters from the same movement that Biden has periodically accused of antisemitism: “They are showing exactly what the human emotion should be as a response to Gaza,” Harris told The Nation earlier this month. “There are things some of the protesters are saying that I absolutely reject, so I don’t mean to wholesale endorse their points. But we have to navigate it. I understand the emotion behind it.”

Three years ago, Harris went on an apology tour after she praised a college student who accused Israel of “ethnic genocide” in a question about why American dollars were going to fund Israel and Saudi Arabia.

“Your voice, your perspective, your experience, your truth cannot be suppressed,” Harris said. “We still have healthy debates in our country about what is the right path.”

(Politico reported that she later called pro-Israel members of Congress and groups including the Anti-Defamation League and Democratic Majority for Israel to underscore her support for Israel.)

The ‘kishkes’ question

Biden, in contrast, has focused on expressing his sympathy for “Jewish students blocked, harassed, attacked while walking to class” and his spokesperson has condemned “an extremely disturbing pattern of antisemitic messages” and “grotesque sentiments and actions” on college campuses over the past year.

His comments frustrated the left, but reflected something that our Israel-based opinion columnist, Dan Perry, wrote about in the wake of Biden’s Sunday announcement:

As a member of the generation that came of age in the years immediately after World War II and the establishment of Israel, Biden has throughout his political career been a friend of the version of Israel that dominated the discourse in those years. It was seen as an underdog country, central to the Judeo-Christian tradition, turned into an unlikely success story by a plucky people marked by the devastation of the Holocaust. To Biden and his peers, Israel was seen as having laid a marker in the sand — not just for the Jewish birthright in the Holy Land but also for Western civilization in the Middle East.

Or, as Abe Foxman put it recently, “In his kishkes, Biden is a Zionist.”

Harris, who was 6 years old when Biden was first elected to the Senate, came of age in a different era. Biden participated in the campaign to free Soviet Jews while Harris raised money to bail out Black Lives Matter protesters.

Harris has opposed federal legislation to crack down on the movement to boycott Israel over concerns that it “could limit Americans’ First Amendment rights.” She sympathized with U.S. Rep. Ilhan Omar, the Muslim-American Minnesota Democrat, when Omar was accused of antisemitism for comments regarding Israel in 2019.

“There is a difference between criticism of policy, or political leaders, and antisemitism,” Harris said at the time.

While many American Jews still relate to Israel like Biden, others have a more ambivalent relationship to the country. Many younger Jews, especially, are equally focused on the suffering of Palestinians, and may resonate with her step-daughter Ella Emhoff’s move to raise money for Gaza on social media.

Kishkes, Yiddish slang for guts, doesn’t clearly translate to policy. Harris’s marriage to a Jew has given her some authenticity in lighting Hanukkah candles and using the word Shoah for the Holocaust. But it seems clear that she is at least starting in a different place from Biden on both Israel and antisemitism.

“The vice president understands how antisemitism is part of a larger scaffold of hatred and racism,” said Jonathan Jacoby, founder of the Nexus Task Force, a liberal group that lobbies Congress on Israel and antisemitism. “I don’t think it’s a contradictory perspective, she just has a more expansive understanding of hatred and racism.”

READ MORE:

- Kamala Harris’ backers say she understands Jews and Israel. Her critics fear her stance on Gaza. (JTA)

- Doug Emhoff: What would it mean if the first first gentleman is Jewish? (Forward)

- Who is Ella Emhoff? How Kamala Harris’ stepdaughter could affect her run for president (Forward)

The post How Kamala Harris views antisemitism differently than Biden appeared first on The Forward.

from The Forward https://ift.tt/tdHAQOe

Comments

Post a Comment