In the town of Ernest Hemingway and Frank Lloyd Wright, a Nazi was hiding in plain sight

This is the story of a respected, beloved janitor who proved his mettle and was promoted to the role of chief custodian at a top public high school in the Chicago suburbs. This is also the story of a volunteer member of the Nazi SS who proved his mettle and was promoted twice during his service as a guard at the Gross-Rosen concentration camp.

And it is the story of a well-off suburb — recognized on a national stage for its diversity and integration efforts — faced with the discovery that these men were one and the same.

For over two decades, Reinhold Kulle made sure classrooms were spotless and faculty had all the supplies they needed. He kept hallways quiet during play rehearsals and made sure students had a safe ride home. But he had also once worn the insignia of the SS-Totenkopf, or Death’s Head, division and guarded a slave labor camp where tens of thousands of prisoners perished. In a marriage application that had to be approved by the Reich, he highlighted his membership in the Hitler Youth and swore to his racial purity.

Kulle failed to mention his Nazi affiliations when he applied for a visa to the United States, where he raised his family and worked at the local school without scrutiny until the government brought a deportation case against him in the early 1980s.

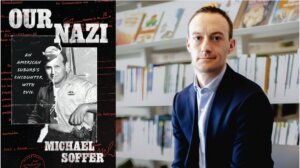

These stories — and how they fit into the larger American contexts of immigration, antisemitism, Nazi hunting and the Cold War — are the subject of the recent book Our Nazi: An American Suburb’s Encounter with Evil.

When the author, high school teacher Michael Soffer, told his students about the Kulle affair, they were certain the revelations about Kulle’s past must have brought about a swift dismissal. The book’s preface, a concise and effective gut punch describing this scene, ends with a dangling, “Right? Mr. Soffer? Right?”

That’s not how the story unfolded, and the students couldn’t fathom why so many in the community — their community — had rushed to Kulle’s defense less than 40 years earlier.

Neither could Soffer, who attended and then returned to teach at Oak Park River Forest High School, in the very same classrooms Kulle once cleaned and later oversaw. Soffer, 39, and certainly his students, were too young to have overlapped with Kulle, but the story felt personal. “This was in my town, this was in my school, in my classroom,” Soffer told me in an interview. They had mutual friends and “all these people and places in our lives that we shared.”

When he and his students couldn’t figure out why so many of those people stood by a literal Nazi, they kept digging. They had so many questions. “I felt like I needed to know,” Soffer said. “I needed to understand.”

Swastikas in a suburban school

The Kulle affair had never been a secret, exactly. Growing up, Soffer said, the story had been a quirk of local history and school lore more than a topic of deep discussion or introspection.

The high school and town had some illustrious alumni and affiliates. “It’s the voice of Homer Simpson, Ernest Hemingway, Ray Kroc, who founded McDonald’s,” Soffer said. “There’s a congressman who made the Betty Crocker character. Frank Lloyd Wright lived nearby. Ludacris went for a year. We have an NBA champion. We have Olympians,” he said. “And then there’s this Nazi.”

“I was always aware of it, and I always knew that it was controversial,” he said — and “knowing that it was controversial always really bothered me.”

Soffer grew up in a Conservative Jewish home where the week centered around Shabbat dinners and shul. His family was part of a warm and active Jewish community but they weren’t living in “the hub of Chicago Jewry,” Soffer said. A teacher once thought he’d made up Shavuot to excuse an absence, he was frequently told to take off his “hat,” and community events were more than once scheduled on Shabbat or holidays. It was “imperfect,” he recalled, but at the time, it was just “part of being an American Jew.”

In most respects, though, Soffer had a happy and meaningful experience as a student at OPRF. He made great friends he’s still close with and had teachers who were so inspiring he scarcely imagined doing anything else with his life except following in their footsteps. After graduating from Brandeis in 2007, he returned as an educator and stayed for nearly two decades before taking a job at Lake Forest High School this fall. At OPRF, Soffer taught U.S. history, psychology, and, toward the end of his tenure there, a Holocaust Studies course he designed and launched.

“On some level, I didn’t want to create the class,” he said. “I felt like I had to.” Between 2016 and 2018 or so, there were multiple instances of explicit antisemitism, racism, and other isms at the school, including graffiti that read “Gas the Jews” and an image of a hand-drawn swastika that was Airdropped to 1,000 phones at an assembly.

“And there was no real larger school response,” Soffer said.

These graffiti and Airdrop incidents came in the weeks after the Tree of Life attack in Pittsburgh. A friend from shul asked Soffer what they were doing at the school. The question echoed and mingled with another he couldn’t get out of his ear. The previous fall, he’d attended a program on the American press and the Holocaust that challenged common misperceptions about what Americans knew and when. Historian Daniel Greene began by asking everyone in the room if they knew what was happening in Syria. Yes, they told him, it was scary. “So,” Soffer recalled him saying, “what are you doing about it?”

These calls to action and the acute situation at the school spurred Soffer to imagine what the perfect curricular response might look like — and he came up with a pitch for a Holocaust Studies course. The school and school board were “wildly supportive” as he developed the class and, through a lengthy formal process, gave his course proposal the green light.

“It felt like something that the district needed, and that I was positioned to do,” he said. This, in other words, was what he could do about it.

The class has a question

Soffer never set out to write a book. He set out to teach. And he was eager to put into practice what education research has shown can be a powerful tool to foster empathy.

The numbers of the Holocaust are so big they can be overwhelming, he said, and in any case, “kids do better with stories.” So he spent a summer researching his wife’s grandparents, who were survivors. “I was able to embed their story throughout the course so that kids could see, like, what did this actually look like for a Polish Jewish family?” he said. “And then I started doing the same thing with Kulle.”

“The story of the Holocaust is a story of Jewish victims, but it’s [also] a story of Nazi perpetrators and of collaborators, some of whom aren’t motivated by virulent antisemitism as much as just, ‘If we clear out this Jewish neighborhood, apartments open up,’” Soffer said. “We have plenty of examples of that.”

By threading throughout the course real stories of two survivors and one SS man — all of whom ended up right there in Chicagoland — “the kids saw that the legacy of the Holocaust is very much still present,” Soffer said, adding that these narratives were “a way to personalize the material.”

The Holocaust Studies course debuted in the fall of 2020, delivered at first on Zoom at the height of the Covid pandemic and then back in the classrooms that had once been under Kulle’s supervision. The elective drew between 50 and 100 students each semester.

The course evolved over time. “You’re always adapting curriculum based on what kids were getting into,” Soffer said. They were interested in post-war social psychology research that got at questions of evil, obedience, and, essentially, “Could it happen here?” And they were fascinated by Nazi hunting in general and the Kulle affair in particular. In time, Soffer would expand the course’s psychology unit and add a Nazi hunting simulation using a list of Dachau guards and a 1975 phone book (a relic he had to explain to his young students).

But first, he followed their curiosity about Kulle. “What a great teaching mechanism,” he thought. “They have a historical question. I’ll model how we do historical research.” They divvied up a digitized archive of local news coverage and scoured the old articles for Kulle’s name, keeping a running Google doc listing his supporters and his opposition. People in the community were still as passionate and emotional four decades later as if it had all happened yesterday. One former school board member called it a “battle zone.” Another recalled a meeting in which Kulle told them he didn’t remember if he’d killed anyone and said, “I just wished we had won the war.”

Soffer recounted sharing what he’d heard with his wife after that phone call. “And she said, ‘So you’re gonna write a book, right?’” he recalled. “And I’m like, ‘No, I’m a high school teacher in the middle of the country. I’m not gonna write a book, but maybe I’ll have a really, really, really cool guest speaker next week.’”

Soffer jokes that his wife was, as usual, way ahead of him. But he eventually saw the light, realizing he was “stumbling into territory that hadn’t yet been fully covered in the historical record.”

There were fantastic books about how Nazis made their way into the U.S. after the war and about the dogged efforts of Representative Elizabeth Holtzman, the Office of Special Investigations, and others to track them down and bring them to justice. But what about an in-depth account of the deeply ambivalent responses neighbors and communities often had when they discovered Nazis in their midst?

As with the Holocaust Studies course, Soffer was uniquely positioned to fill this gap. Personnel files and school board notes were in the building. Prominent figures in the story were in town. And people who would understandably refuse an outsider might talk to their neighbor or colleague.

As it turned out, this high school teacher in the middle of the country was writing a book after all.

A perfect case study

A seasoned educator like Soffer will tell you that lessons can become loaded when they hit too close to home. “When you’re talking about American politics, people can get defensive,” Soffer said. “It’s our country, that’s maybe my great grandfather, or it’s my town.” But when it came to teaching the Holocaust, he thought, “there’s nuance, but in terms of who the perpetrators are and who the victims are, there’s not.”

The more he learned about the Kulle affair, however, the more he saw that in cases of Nazis who’d built new lives for themselves in America, public perceptions weren’t so clear cut. Our Nazi does a skillful job using punchy, engaging prose to weave together the history of Oak Park, the personal trajectory of Reinhold Kulle, the story of his investigation and deportation proceedings, and the surprisingly tense debate that swept the town, all against the backdrop of accelerating Nazi hunting efforts by the U.S. government.

In so many cases across the country, Soffer explains, the response to revelations of a friend or neighbor’s Nazi past followed a pattern. First, deny. The loving father who tends to his garden couldn’t possibly have done such things. Second, downplay and justify. Maybe he was there, but he didn’t have a choice, and he never personally hurt anyone. Third, recast the perpetrator as the victim and insist on redemption. Why are you ruining his life over something that happened so long ago? This last step often veered into blatant antisemitism, portraying efforts to bring Nazis to justice as “Jewish vengeance” juxtaposed against “Christian forgiveness.”

Kulle’s story “was like this perfect case study,” Soffer said. “If there was one place that would have been different, it would have been Oak Park, right?” The town had won national awards for its commitment to integration and diversity. And Kulle didn’t work in a factory. “He worked in a school, which raises the stakes significantly.”

“This is the one that should have been different from the others and it wasn’t,” Soffer said. “It’s really easy when the bad guy is the Nazi in Indiana Jones,” he added. But “Kulle doesn’t look like that by 1982. He’s got the slight paunch of middle age and he’s a doting grandfather and it’s complicated, because human nature is complicated.”

The three-part response pattern — which might sound familiar to contemporary readers who’ve followed cases of rape and sexual assault — points us toward one of the main arguments of Soffer’s book: People’s reactions were not so much about Kulle as they were about themselves, their relationship with Kulle, and the implications for their self-perception.

“When I find out that I’m friends with this monster, does that make me a monster?” Soffer said, explaining the circular thought process. “If I’m a good person, he must not be a monster, right? Because otherwise I wouldn’t be friends with him.” The same logic was true in Oak Park and has long informed American perceptions of the U.S. response to World War II.

“Everyone in the book, no matter where they stood on this issue, saw themselves as a good person, doing the right thing,” Soffer said, whether they were calling for Kulle to be removed immediately from the school and placed on paid administrative leave or rallying for him to keep his job, fundraising to help with his legal fees, and throwing him a retirement dinner.

While most readers are unlikely, at this point, to discover a WWII-era Nazi at their local school, “we often encounter things about someone we thought we knew that are troubling,” Soffer said. “What do we do when we find out something horrible?”

What many in Oak Park did in the ‘80s might be profoundly frustrating to Soffer and his readers, as might the fact that Kulle lived a free man until he died in 2006. But Soffer, ever the teacher, couldn’t help but point out another, more uplifting takeaway.

“He doesn’t end up in jail, but he has to leave,” Soffer said, referring to Kulle’s ultimate deportation to Germany in 1987. “In some ways, it is a story of justice and of heroes,” Soffer added, including the indefatigable lawyers and historians of OSI and two Jewish women in particular — RaeLynne Toperoff and Rima Lunin Schultz — who were vilified for leading the local charge to remove a Nazi from their school.

“These were heroes who, through sheer force of moral suasion, held a community and a country to do what it was supposed to do,” Soffer said. So although it’s not what he initially set out to do, he said, “I felt like I owed it to them to get this book written.”

The post In the town of Ernest Hemingway and Frank Lloyd Wright, a Nazi was hiding in plain sight appeared first on The Forward.

from The Forward https://ift.tt/xkV54ih

Comments

Post a Comment